Sibling Bond Beyond Years

Only a few hours after I hugged my mom goodbye for the next nine days of summer camp, I pulled out a small photo wedged between my sunscreen and toothbrush — it’s of my brother, Oscar.

While most 13 year olds would worry about phone withdrawal and losing their Snapchat streaks while away at summer camp, I was dreading being away from my two-year-old brother.

I was a 6th grader at Westwood View Elementary when Oscar Norman Winkler entered the world Sept.13, 2013 at 1:26 a.m. Now four years old, Oscar and I share a unique bond — despite our 12 year age gap.

It’s through the hours of bottle feeding, rocking him to sleep and bathing him that my mom coined me Oscar’s “second mom.” With a dad who frequently travels for work and a mom who works long hours as nurse midwife, I often found myself turning down party invitations and sacrificing precious homework time to watch Oscar.

I love Oscar, but any teenage girl would offer up a slight eye roll to missing out on ice cream runs or nights on the Plaza with friends.

But as I grew closer and closer to Oscar, I realized how invaluable my time was with him. Along with allowing me to grow closer to him, all the time changing diapers, walking him to the park and teaching him to do a puzzle also taught me time management that would help me as my homework load increased.

The responsibility of taking care of a child prepared me for my first job as a lifeguard and swim instructor when I needed patience to teach a toddler how to flutter kick. Even the mere act of prioritizing family over myself taught me more about love and selflessness than anyone could verbalize to me.

And though it may sound corny, Oscar, with his golden ringlets of hair and single dimple on his cheek, was the one who helped me discover what love really was. Not the sappy stuff you see in romance movies, not a word with four letters you can throw around — but the act of always putting that person before you. Whether this be as simple as going to Chipotle for Oscar’s favorite meal when I’m craving Chinese food, or sacrificing my own sleep to get him to bed at night.

Now Oscar’s growing up and I feel like I’m watching my own son learn to count to 13 (we’re working on getting to 20). It’s hard to ignore the impending time in a few years when I’ll be packing my bags again for college.

I’m dreading leaving my Oscie baby again for college — this time for even more than nine days. I’ll pack a collection of photos of Oscar when I head to college, but I know I’ll always have our countless memories and the things he taught me when he was only a fraction of my age.

Diversity Committee Panel

“What is it like to be the only African American students in the class when reading Huck Finn?” Principal John Mckinney said.

The first diversity inclusion committee panel discussion, organized by the Parent Teacher Student Association was held Jan. 29. The panel is made up of nine members consisting of current and former students, parents and community leaders ranging in age, gender and religion.

The members each had time to speak about diversity issues at East, good experiences and bad. The goal was to better educate the East staff and to prepare them to deal with situations that may make them uncomfortable.

East has an 8 percent hispanic and latino population, and just under 2 percent black. Mckinney organized this panel to help find ways to make the minorities feel safe, welcomed, appreciated and included.

“Principal Mckinney has been trying to give teachers more tools to prepare for the changing world that we have here,” social studies teacher David Muhammad said.

Muhammad explained that race is a tough issue for everybody to discuss. According to him, teachers may feel targeted if a student accuses them of discussing a sensitive subject in the wrong way – they may not realize the discussion is unintentionally making a student feel uncomfortable.

“If there [are] 100 people in a room and all of them look different than you, you are going to feel uncomfortable,” Mckinney said. “We recognize that. We don’t see it as a flaw, but as something needed to be fixed.”

The staff has identified an area for improvement regarding cultural differences to concentrate on: getting to know one another better. Mckinney feels that the stronger the relationships made, the more understanding people have of one another.

He stresses the fact that he wanted the students’ perspectives on different situations presented in learning environments and how they affects them. According to Mckinney, ages 14 through 18 are monumental in a child’s life and how shape how they view the world.

“We come here day after day, year after year,” Mckinney said. “Students are here for only four short years, so we want to make those years very meaningful and make sure we prepare students to be successful after they leave here.”

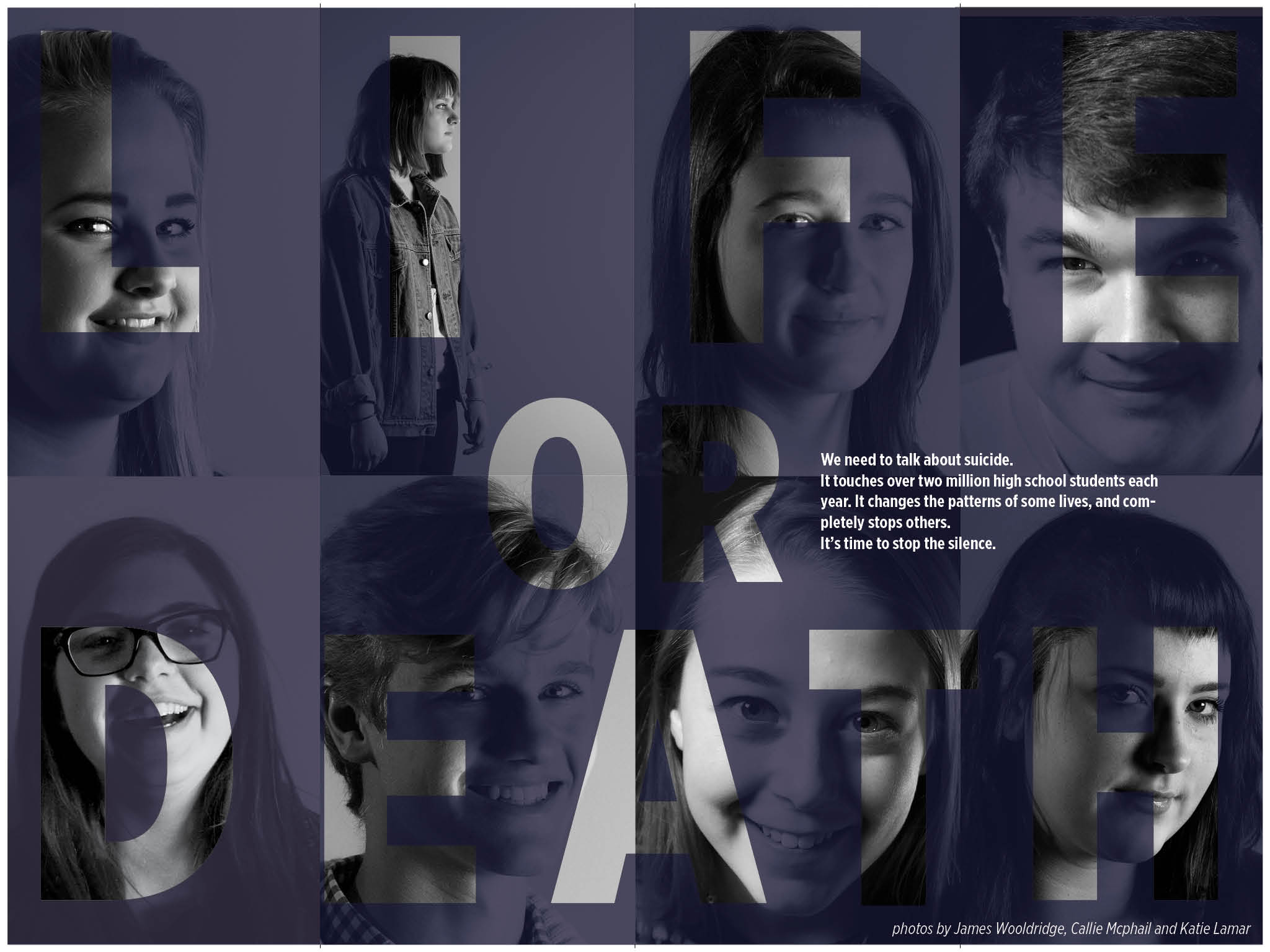

The Suicide Project

“I remember just becoming overwhelmingly angry at my depression,” Evan said. “I started waking up every day feeling like I was going into a dogfight. And I wanted to just hit my depression in the face to make it go away. I wanted to win.”

Winning The Dogfight

By Julia Poe

Every morning, senior Evan Rose repeats the same saying. It’s tacked on his bulletin board, right above his bed. It’s his daily prayer, his mantra.

God, give me the serenity to accept the things I can’t change, serenity to change those I can, and wisdom to distinguish between the two.

Evan found the prayer his sophomore year, buried among the pages of “Meditations” by Marcus Aurelius, his first book of philosophy. He was a 16-year-old with a brand new prescription of antidepressants whose life was consumed with numbness. For almost five years, Evan had tried to hide his depression, stifling it throughout the day as he surrounded himself with friends, letting it tear him apart each night.

Then Evan found his prayer.

“I remember just becoming overwhelmingly angry at my depression,” Evan said. “I started waking up every day feeling like I was going into a dogfight. And I wanted to just hit my depression in the face to make it go away. I wanted to win.”

It started in fifth grade. Depression was a fog that slowly rolled into Evan’s mind, coating him in a gray indifference and distancing him from his friends and family. He cried often, came home from school and dissolved into a mess of tears and anxiety.

“I started worrying a lot when I was in fifth grade,” Evan said. “I started to question things, like ‘Is there a God?’ or ‘What’s the meaning of life?’ and I was way too young to comprehend that. It made me anxious, all the time. I didn’t understand my own life.”

The depression clung to Evan in middle school. He was constantly afraid that he would cry in front of his friends. So he perfected a mask, a disguise — how to smile, how to joke and make fun of his friends, how to avert attention from himself.

Evan stopped spending time at his house. He did homework with friends, ate dinner with friends, played video games with them and slept at their houses. He was afraid of being alone, so he refused to spend any time on his own. And whenever he was with other people, he wore his mask — happy, cheerful, funny. Fake.

And that’s when Evan began to think about killing himself.

“It was home,” Evan said. “I felt so at home in this mask, because it gave me the ability to actually function. But at the same time, I knew that it wasn’t me. It was so fake to who I was, so wrong, and underneath all of it I was still the same scared little kid.”

When he was alone, his mind turned in on itself. Depression became an overwhelming pressure each night, crushing his mind with unnecessary questions.

He never dealt with specifics, never considered where or when or how. He loved his parents, his friends too much to die. He didn’t want to hurt anyone. But thinking about suicide made Evan feel in control.

“There was this feeling, this understanding that I could end it all if I wanted to,” Evan said. “And I never tried. I never would have. But I had power over that, and having power over my death kept me going through a lot of nights.”

Freshman year, his mom sent him to therapy. It didn’t work. Evan hated trying to assign words to his emotions. He stayed in therapy for a three months, just to please his parents. After that, Evan quit therapy — but he was newly prescribed with an antidepressant aimed at curbing the chemical causes of his depression.

“That was when everything started to change for me,” Evan said. “I realized that I have to put meaning into life. I have to wake up every day and find a purpose for myself. It’s not going to come to me; it’s going to be something I go find and create and explore.”

Evan began to find solace in philosophical writings, such as the work of Lao Tzu. They answered the questions that had plagued him since fifth grade — about the purpose of life and the existence of a god — and at the same time, they helped him find purpose in daily life.

His attitude towards his depression began to change. Before, it had overwhelmed him. Now, it started to piss him off.

“You get to a certain point, and this has been your life for years, and you just say, ‘Enough,’” Evan said. “It took awhile to overcome, but I was just so mad. I fought it every day. I fought it every day until it was gone, for good.”

It took over two years years of forcing himself out of bed, of distancing himself from negative friends, of reading and reflecting and pushing away depressive thoughts. But after two years, Evan defeated his depression.

It was a slow process, and a daily one. He realized that when he wore a mask over his depression, he was constantly trying to please others. He became adept at faking laughs, at poking fun at people to stay popular with people he wasn’t sure he liked. To defeat his depression, Evan stopped faking it.

He found success in little things. Having an honest discussion with a friend late at night. Reading a new book of philosophy and finding peace with a new part of his life.

And he stayed angry at his depression. He approached it like a battle, throwing punches at the thoughts that used to send him into suicidal spirals. He kept swinging until he felt positive, until he went days without anxiety. He kept fighting until he was free.

Now, Evan feels like he can finally take his mask off. He’s spent seven years wearing it, learning how to smother his emotions and his personality.

And finally, he’s getting used to being himself.

“I feel great,” Evan said. “I feel strong. I feel brave. I love life. I live for myself more, now, but I also live for others. And I feel like, for the first time, I don’t have to worry. I’m finally myself, and I couldn’t be happier.”

The Secret of Happiness

By Julia Poe

Her scars are healing.

They criss-cross her arms, her thighs. They’re mostly the work of the razors she stole from her dad, with a few here and there from a Bic lighter. She doesn’t hide them anymore. It’s winter now, but in the summer she wears short sleeves, T-shirts, tank tops.

She hasn’t made a fresh cut in over four months. She’s happy.

Sophomore Maddie DeTommaso used to hide. She wore cardigans and sweaters to cover her forearms, constantly tugging down the sleeves so that scabs wouldn’t peek out.

It went beyond embarrassment. Maddie hid her scars because she was afraid — of her parents’ disappointment, of her classmates’ taunting, of herself.

She’s not afraid anymore. She’s strong. She’s happy. But three years of fear almost stole Maddie’s life away from her.

The fear started in sixth grade. Maddie was the kind of kid who cried when people squished bugs. She cradled life delicately. And when she was bullied, each taunt and shove cut more deeply.

Maddie remembers being called names. Being told she was fat. She remembers sitting alone under a tree at recess, crying and then hiding those tears. She remembers running home each day to fall asleep in bed, exhausted by the colossal weight of living each day.

“I was just tired, every second,” Maddie said. “There was this feeling of hopelessness, from a very young age. Honestly, when you feel that there’s no hope and you’re in sixth grade, you don’t think there’s any point.”

At first, she tried to change. As a sixth grader, Maddie started her first diet. And her second. And her third. She tried cutting carbs, then protein. Then she stopped eating at all.

It didn’t help.

She couldn’t shake the feeling that someone was watching her, always. At home, it was her parents, constantly nervous she would dissolve into tears again. At school, it was everyone else. Teachers, students, even her friends. She thought she could feel them watching her, whispering, pointing out her flaws.

“I just wanted to hide,” Maddie said. “I wanted to be small, small enough that I could get away from everyone looking at me. I wanted to disappear.”

Her parents had no idea. Her mom, Doreen, knew that Maddie was a quiet girl, gentle and even fragile at times. But at the time, she had no idea that her daughter was depressed.

“I look back, and I see so many signs,” Doreen said. “She spent a lot of time alone, in her room, and she was so detached. She wanted to please us, so she hid as well as she could. But I wish I had just known what to look for, because it is obvious to me now.”

Life got harder. The next year, seventh grade, was a year of firsts.

There was her first boyfriend. Maddie thought she loved him. When he dumped her after a week, she felt lost, lonely. She would date 14 more boys that year — each one short lived, each one a blow to her confidence.

She thought they would fix her. She was wrong.

There was the first time she cut. Most of her friends were online, met on Facebook and Tumblr and chat rooms. Most of them were depressed.

They showed her pictures of their wrists bloody from fresh cuts. They told her it helped. She believed them — it hurt, but it helped — so she kept doing it. On her wrists, on her thighs. It was a distraction.

“I remember the first time I cut, I was just thinking about how much it would hurt, but how I had to do it,” Maddie said. “Then it got to the point where I couldn’t wait to come home and do it, where I was thinking about it all the time. I felt like it saved me.”

There was the first time she tried to kill herself.

It was in the Village, after school. The few friends she had were making fun of her. Again. The exhaustion was swallowing her, the anger was swallowing her, so she climbed on top of a bridge and tried to figure out how to fall precisely on her head.

Her friends pulled her down. She couldn’t decide if she was relieved or angry. She tried two more times.

The second time, she swallowed enough ibuprofen to kill herself, then leaned back on her couch and waited. Her parents came home and found her too early. At the hospital, they made sure her bloodstream was free of any lethal painkillers, but they didn’t notice she was still stuffed with self-hate, with anger, with depression.

So she tried again.

The last time was the summer before eighth grade year. Boyfriend number 15 had just dumped her. Her classmates at school made fun of her cuts in the halls. In one of her last classes of the year, a boy pretended to hang himself, laughing, “Look at me, I’m Maddie DeTommaso.”

“It’s unbelievable, the cruelty that she was experiencing during those days,” Doreen said. “There’s only so much you can do as a parent to protect your child from that. We did what we could, but I always felt like it wasn’t enough.”

She was afraid to talk to her parents about the things in her head, and she was definitely afraid to tell her friends, who seemed to be dwindling each day. She felt alone.

“I remember taking the pills and then thinking, ‘Oh God, I just did that,’” Maddie said. “I think I knew it was the last time at that point. I knew something had to change. I’d either die or I’d get out of this hole and make a change.”

She lived. And everything began to change.

In eighth grade, Maddie stopped talking to people who hurt her. She found a group of people who liked art and music, who didn’t want to talk about depression. And as her classmates grew older, the bullying began to slow down.

She stopped relying on long-distance friendships. She spent less time online chatting with her Facebook friends, who encouraged cutting and suicide. Instead, she dove into art, into songwriting. And she began to feel her mood lighten.

“Before things got really bad, we had no idea what she was fighting against,” Doreen said. “Once we knew, we fought it together. It was little things, just drawing her out of her room, finding ways to separate her from negative people and the bullies. It took a lot of trial and error, a lot of just talking things out as a family.”

It wasn’t easy. It wasn’t quick. It took three years of choosing to be happy, choosing to pick up her guitar instead of her razor. It took coming to East, where students don’t poke her scars anymore. It took time.

But now that time has passed, and Maddie looks toward the future, a future without depression.

“What’s happiness?” Maddie laughs. “Happiness is feeling free.”

She remembers the first day she was acutely happy. It was in the summer, at an art show, with a small group of friends. They found an old swingset and clambered on. Maddie and her friend competed to see who could swing higher, pumping their legs to gain more momentum.

The wind blew her hair back, away from her face. She closed her eyes, gripping the chains of the swing tighter, and realized she was happy.

“I thought, ‘This is what this feels like,’” Maddie said. “It’s being with a group of people who love me, being happy who I am, not feeling like I’m being watched or have to hide. I want to feel like that for the rest of my life.”

“I’ve gotten to the point where I’ve kind of realized that [self harm] is not really helping anything,” Claire said. “Hurting myself isn’t going to do anything to make myself feel better. In all reality, it’s just going to make things 10,000 times worse.”

A Second Chance

By Hannah Coleman

Today is a self-harm day, she thought.

She began to write.

I’ll use pills today.

Why? Because my parents can’t see me hurt, that’s why. They can’t see me with blood. I couldn’t do that to them.

It was entry number two that day. Senior Claire Ridgway hastily scrawled her secretive message into her black and white Five Star composition notebook.

She hadn’t let any tears fall. She was good at that. No one knew she wrote in her notebook every day. Pages crammed with feelings she etched out every time she felt something. How she was bigger than most girls. And shorter than most people she knew.

She carried it in her backpack around middle school constantly, a heavy-bound notebook of emotions that added onto the weight she already had to carry every day.

Claire never knew anything outside of her own insecurities growing up. To her, her problems were normal. Everybody had them, right? She thought everyone lived the way she did, with the dull throbbing of her poisonous thoughts constantly tugging at her consciousness.

When Claire got into middle school, she realized that she was just a sheltered rich kid living in Mission Hills. She knew nothing of the world.

The world had kept hidden from her the sight of the perfect girls that roamed the halls. The ones with perfect bodies, swarmed with friends, free from social anxiety.

Not everyone was like her. Instead, she found she was different from everyone.

And it almost killed her. Four times.

She fell into a foggy depth that she couldn’t pull away from. To her, it was nearly impossible to separate her feelings of self-hatred from herself.

And yet no one knew about it.

The only evidence of a crumbling middle school teenager was her notebook, a scrawled documentation of her attempts at suicide. The blurred moments of shoving pills down her throat, no specific number, just as many as she could. She couldn’t remember the rest, just that they weren’t enough to kill her.

Throughout the rest of middle school, Claire found comfort in “the wrong crowd.” They made her feel normal. As a then-13-year-old, Claire found herself drinking and doing drugs, intoxicating herself and her relationships. She kept falling deeper into the hole she was digging for herself, not realizing that it would eventually lead to her first attempt at suicide.

Without confiding in anyone about her situation, she severed any possible contact or chance at hope with someone who cared. Her self-hatred deepened further. Loneliness is the first sign that someone is an outsider.

“I hurt myself in ways that no one could ever find out, or see, because I didn’t want people to know, obviously, I don’t think anyone really wants people to know. Since I didn’t tell anyone, it got really bad for a while, and I was just in my own little bubble of self-hatred.”

But eventually, Claire was found out. She was right, she could hide herself visibly from the world. Her outer image gave away nothing. But her sporadic moments of vulnerability gushed onto the papers of her notebook gave away everything, and Claire’s nanny, who found the notebook, was immediately concerned.

Then counseling began.

But Claire was a good liar. Even with the circumstances, Claire convinced her counselor that she was ok. She smiled as big as the pain that was within her, and didn’t let a single tear drip from her eyes. She told her that she just felt bad sometimes, and that was all. Her counselor would nod enthusiastically. She believed her.

Claire didn’t want to deal with the added distress of having to involve antidepressants in her life, so instead she lied about her pain. She said she didn’t need it. She didn’t need help.

“Counseling didn’t really help me all that much, I didn’t really feel comfortable in that environment, and I think that’s my fault more than anyone else’s and I didn’t say what I needed to say to get help, but mostly it was a self-help type of thing,” Claire said.

Claire knew that she could never accept the help of others, or try to pursue it. Talking about herself, the very thing she hated, frightened her. Her parents couldn’t know. They would be worried, they were too good to her, they didn’t deserve that. She couldn’t tell her brother, he was the top in his class, doing things she felt she could never do. She couldn’t let him see the disappointment that she was.

But when all of Claire’s relationships dissolved, and when the reality of that sank deep within her consciousness, she realized that she really did have nothing. And those thoughts so familiar to her notebook resurfaced. The ones about suicide, the ones about killing herself.

Death is better, she thought.

Death will make me happier.

Everything will be happier.

Sitting at her lunch table in the eighth grade, alone, the day the last of her so-called friendships dissipated, Claire felt nothing.

If the group of girls at the lunch table sitting next to her at the peak of her misery hadn’t motioned her over, Claire would be dead.

She would be lying motionless, deadly silent, a sleeping remnant of a person who couldn’t feel. That’s how she pictured herself dead: without all of the blood. Just a stony memory.

But that hallucination faded away. She had new friends. Ones that cared, ones without all of the baggage that came with being in “the wrong crowd.”

It was the first sign that something good could happen in her life. She felt like she didn’t need people, but she needed them for herself, so she could get past everything on her own. She wanted to do it on her own.

Sometimes she wished that someone had been there for her to force her to talk, to open up even though she didn’t want to. But she realized she could do that herself. She began to recognize that with the pain she was feeling, self-harm would worsen.

“I’ve gotten to the point where I’ve kind of realized that [self harm] is not really helping anything,” Claire said. “Hurting myself isn’t going to do anything to make myself feel better. In all reality, it’s just going to make things 10,000 times worse.”

Pulling myself out is the best thing I can do, she would think.

And she did. She forced herself to stop wearing full makeup when she used to cake it on. She let her blond hair grow out and she quit messing with it constantly. She wanted to stop having to feel perfect.

“I tried to get myself to worry less if people liked me and more about school or other important things going on in my life and just tried to smother my bad feelings of myself with things that I liked about myself,” Claire said.

She felt the only way to accept herself was to be natural. To accept herself and her body for the way that it was instead of hiding under makeup, or doing her hair a way she didn’t want to.

Her appearance wasn’t the only thing she strived to change for herself. She talked to others who dealt with depression and social anxiety, and the connection eased her mind. For once, she didn’t feel like she was different than everyone else, she realized that others struggle too. The fact that there were so many others with the same problems gave her the most hope she’d ever experienced. Because not only had they faced death, but because of it, they chose life. And that’s what Claire did.

Claire still has bouts of depression. The memories of attempting suicide four times won’t ever die down. But she’s satisfied with what she’s done. She did it herself, she made the most important realization she would ever make: death isn’t something that could make her happy. She couldn’t be happy if she was dead. To be alive, and to be happy alive, is the only chance you have at it. And she realized that death would end that chance.

Suicide In Teens

Written by Michael Kraske

For youth between the ages 10 and 24, suicide is the third leading cause of death. It is estimated that approximately 2,000 adolescents aged 10 through 19 commit suicide a year, and two million attempt suicide.

Suicide can stem from different factors depending on the living situation, social environment and age-related life-situation of the person involved. It is different for both genders, for racial and ethnic groups, for persons struggling with LGBT issues or in some other way feeling disenfranchised. It’s also different for different persons from other parts of the United States.

That being said, there are also some elements that are common to almost all cases.

According to Bill Geis, professor of psychiatry at the UMKC School of Medicine, there are many important differences in suicide and suicide attempts in adults and youth. One of the main differences is how in young persons, the most glaring issue is how frequently suicide attempts are driven by an impulsive crisis.

“In approximately a third of youth suicide attempts, the decision to make an attempt is made the same day the (impulsive) act occurs,” Geis said. “Our studies suggest that people are often in an altered state when this happens, and the person is in no way thinking clearly about their situation.”

Geis also says that there are strong differences in how adolescents become suicidal based on the type of school they attend: urban, rural, suburban and parochial. According to Geis, in urban (and some non-urban) areas, the stresses and risk factors often come “from the outside” in the form of violence, drug activity and lack of adequate resources, like housing, food and places to hang out. This builds over time so that one’s “bucket just gets too full.”

In parochial and suburban schools, such as Shawnee Mission East, these external intrusions aren’t as strong. Students are impacted by internal impingements such as pressure to succeed, constant competition and the feel of the need to win at everything done does.

“This is training for the real world, but sometimes the pressure is too much, just as a star athlete can be performing well, but then a genetic defect leads to a knee injury,” Geis said.

But many crisis situations also share common traits. According to Geis,almost all suicides start with some overwhelming sense of pain. That pain can be caused by trauma dating from early in the person’s life. The pain some experience can be genetically based and passed from parent to child.

“Often, persons at risk carry genetic vulnerabilities to being exquisitely sensitive to loss, rejection or personal disappointment,” Geis said.

This pain might include feeling like one does not belong, feeling bullied, relationship break-ups, family stress and other social stressors.

These days, scientists are focusing on six genes that are associated with negativity and impulsiveness.

“The person at risk typically has a point of view wherein they tend to see things in highly negative ways,” Geis said.

According to Geis, when individuals are most suicidal, they can be in an altered state of mind and only later realize their thinking has changed dramatically.

Maureen Underwood, clinical director of Society for the Prevention of Teen Suicide, said teenagers often have a distorted view of time.

“If you’re thinking like a teen, you’re thinking, ‘My life was terrible two months ago, it was terrible two weeks ago, and it’s terrible today, it must be terrible forever,’” Underwood said. “So there’s this inability to have enough life experience to know that you can have rough times, but you can also get through them.”

Underwood said that the scariest part of suicide in young people is how intentional the act is.

“Someone makes a choice to end their life,” Underwood said. “That’s terrifying for all of us, because it cries in the face of survival instinct. To think that you somehow disconnect, just for a couple seconds, from life — that’s it. With drunk driving, kids don’t have the intention of dying. With suicide, the intention is to end a life.”

Bringing The Discussion To East

Written by Sophie Tulp

It’s East guidance counselor Becky Wiseman’s worst nightmare. That a student could be struggling and she wouldn’t know about it. That a student could choose to attempt suicide, before receiving help. It’s a concern that weighs heavily on her mind. Wiseman worries that students and staff might not report concerning behavior, and she wants to change that. She and Principal John McKinney are re-evaluating how they can start a conversation about suicide awareness and prevention in school.

“It’s my biggest fear that we couldn’t reach a student before they made that decision, and give them time to reconsider and choose life.” Wiseman said. “I think in some ways people worry ‘am I making too big of a deal?’ ‘Is it really just somebody having a bad day?’ Teachers and students have that hesitation, but we need to start having this conversation in school so they know it is okay to talk address.”

At Olathe Northwest High School (ONW) two weeks ago, two young women ended their lives over a span of a single weekend. The deaths rocked the communities surrounding ONW. In the aftermath, East counseling staff and administration are assessing how to better address the topic of suicide in the school setting, to open up the discussion and prevent future tragedies.

At the staff meeting on Nov. 12, Wiseman urged faculty to report to her if they see anything, hear anything or even just have concerns about a student and their mental well-being.

Although no specific programs have been initiated yet, the event at ONW is prompting a discussion of suicide that will be different from those in the past. Currently, the major roadblocks are finding the right forum to have the discussion, and finding the most effective way to convey the serious topic. And that means re-evaluating practices used in the past to address suicide.

Wiseman’s biggest worry is finding the right way to have the conversation with students. Currently, October is set aside as Red Ribbon month, covering suicide awareness, alcohol and drug abuse and anti-bullying all at the same time. This limits the emphasis the school can place on a single topic. To Wiseman, condensing everything into one month means not taking time to appreciate each issue appropriately.

“It all happens within a month period,” Wiseman said. “Do we have a discussion during that week? Is it brought up in an assembly? Is it in a curriculum type forum — health classes or psychology classes? It’s not a question of do the adults around here care, but where is a forum where this discussion can happen.”

Up until recently, Wiseman says people have shied away from discussing suicide prevention or awareness, because they do not want to say the wrong thing — adding to a ‘let’s just not talk about it’ mentality.

Early in her career, Wiseman was told that if you talk about suicide, you will make people who are contemplating it follow through. Now, Wiseman increasingly sees this old idea being cast aside. In her extensive school counselor training courses, she learned that current research actually disproves this old outlook, and opening up schools to address the subject more publicly.

The National Institute of Mental Health says that school and community prevention programs are most effective when designed to address suicide and suicidal behavior as part of a broader focus on mental health. This means not just lecturing students about the devastating effects of suicide and therefore desensitizing them to it, but teaching coping skills in response to stress, substance abuse and even aggressive behaviors that students naturally encounter in this phase in their lives.

Schools across the country are trying to incorporate these mental-health based discussions, proven to be most effective, into a conversation with their students. American School Counselor Association member and former President of the Colorado School Counselors Association Sandy Austin deals with the after affects of suicide in her school community frequently. Recently she dealt with the loss of three students to suicide in the span of a single month.

“[Following the tragedy] we went into all of the english classrooms, because we knew we could hit every single student at school that way,” Austin said. “We needed to get students to come to us before problems occurred, so we knew we had to change the culture of the school to where the students felt comfortable to come and talk to us and let us know if they were having [suicidal thoughts].”

Following the traumatic events, Austin and the school initiated multiple programs and clubs with a focus on reaching out to students and showing that there is someone in the school who cares. An anonymous tip box was placed near the office, and at the end of the semester 42 students were put on 72-hour watches for their serious suicidal thoughts. Austin says the tip box lead to potentially saving those 42 lives.

Another program, Believe It Or Not Someone Cares Club (BIONIC) is an example of spreading awareness and preventing suicide in a way other than a formal assembly discussion.

BIONIC Club member’s are split into three teams to address the issues that the students who killed themselves suffered from, leading up to their deaths: extended Illness, death in the family and academic stress. BIONIC club member’s visit students in the hospital with gift packages, make sympathy cards and pies for students who lost loved ones, introduce new students to the school and send cards to students who are out of school sick for more than five days.

BIONIC Club’s mission was — and still is — to reach as many at-risk students as possible to promote an environment where students are comfortable coming to the adults in the community for help. And it was a program that Austin says had made all the difference, even prompting teachers to tell her it is the single thing that made the school a more caring climate.

Two years later, more than 700 schools worldwide have contacted Austin, in hopes of starting their own BIONIC clubs.

Dr. Bill Geis, Director of Behavioral Health Research for the UMKC School of Medicine, has found that before suicide prevention is initiated in schools, only about 40 to 50 percent of students say they are willing to go for help if they feel suicidal. After prevention is initiated in schools that focuses on promoting help-seeking, up to 90 percent of students say they would get help if they find themselves in a crisis.

“In our work in schools, we are trying to promote the value of self-advocacy at every age,” Dr. Geis said. “Students have to be willing to seek medical and behavioral help to to fine-tune problems and to avoid the long-term effects of stress.”

As the third leading cause of death in young adults aged 10 to 27, McKinney says suicide is a topic the school cannot shy away from. It is a responsibility of the staff and the administration to look out for the students who spend half of the day under their supervision.

Both he and the Johnson County Crisis Center agree that children are more likely to come into contact with somebody who can help them if they are having suicidal thoughts in the school setting.

“We would be irresponsible if we weren’t talking about it straight up.” McKinney said. “As we find ourselves faced with this tragedy I just think that everything that involves the students [here], this school has a responsibility to address. I don’t follow you home on the weekends and see what you are doing, but if you call me concerned or upset, I am still on the clock. I get you for four years and I don’t stop caring even if we are not in school.”

Suicide Romanticization and Glorification

Written by Stella Braly

Open the page. Refresh the feed. Refresh the feed. Refresh the feed.

Checking social media in this generation has become a habit. It’s done easily, without giving too much of a thought.

Social media has become a way to not only share thoughts, images and work, but also a way for people with like minds to meet. In some cases, however, social media can be toxic.

These days, it is nearly impossible to open Tumblr without seeing some pale, bone-thin girl sitting outside with rough self-harm scars across her legs, holding a cigarette and maybe a flower or two for aesthetic purposes. Or maybe even something along the lines of a black and white photo of a withered and sad girl coupled by a sad quote about how great being skinny feels, or how beautiful sadness is.

Let us understand that sadness is not beautiful.

Mental illness, self-harm, eating disorders and suicide are not beautiful.

Pretty girls do eat. Black and white photos of cuts or burns with a quote about dying written over it isn’t “soft grunge”. And most of all, death is not beautiful.

“Misery loves company and no one wants to be alone,” Christine Oliver, a counselor at Indian Hills Middle School (IHMS), said. “So, when someone is overwhelmed by sadness it is easy to seek out others that feel the same. Since that relationship is only based on shared sadness, the focus becomes finding ways to ‘fit in.’”

Fitting in seems like a increasingly difficult thing to do. There’s groups for everything — art, sports, even “Doctor Who” has a group whose friendships are built on their love of the show.

Tumblr, a photo and text post sharing website, has over 140 million blogs. It’s popular for those who don’t necessarily fit right in with the set groups of school or work. Users thrive on this site because they can be invested in many different communities. And while friendships made through similar interests are healthy relationships, friendships built on depression and shared hashtags like “thinspiration” or “thigh gaps” don’t always seem to last. If anything, they have a negative impact on the participants’ mental health.

“Those relationships are based only in shared pain and it leads to kids normalizing behaviors like cutting,” Oliver said. “Unlike most adults, teens are still defining themselves and deciding what kind of person they are. When you couple the constant negativity with the process of trying to define oneself, the results can be troubling because a balanced picture of life is missing.”

Being surrounded by photo after post after video of negativity creates a negative person. And while it’s easy to deny that it could possibly affect someone, it’s also very arguable that it does.

Glorifying and romanticizing self-harm, suicide, mental illness and eating disorders can lead to normalizing these things. It creates a distorted vision of depression and other mental illnesses, and also leads to those feelings of hopelessness that the posts depict.

That’s not to say that what these people are feeling is not real. To them, this could be the realest thing in their lives at that moment, and maybe for a long time. They do feel valid emotions, but because of the way they are seeing depression and suicide expressed through social media, their views are altered to think it’s beautiful and lovely, just as the posts show it to be.

No one knows exactly why people post these romanticizing posts, but there are many explanations that experts have as to why these teens feel the need to glorify and romanticize something that should definitely not be viewed in that way.

“I think maybe in our society the idea is that it’s not okay to be just okay.” Becky Wiseman, East’s social and personal counselor, said. “You either have to be the brightest, strongest, best looking, richest or most powerful to be something in this world. So if I am not any of those things then something ‘has to be wrong with me.’”

Some people say that that posting these photos and words is a fast and easy way to receive acknowledgement for the pain these teens face. Others say that some just want to fit in or feel special.

In my opinion, just stop. Whatever the reason, think before posting. People need to stop treating serious things like a fashion trend or a competition to have the most “soft grunge” look, the most followers on a pale blog, the skinniest thighs, the most mental illnesses, the most suicide attempts, the deepest and most scars on their body.

What these teens don’t always realize is that while they play “the most” game and try to see who gets the most reblogs or likes, they are messing with serious things that can affect someone for the rest of their lives. If they have a life left to continue. Romanticizing these unhealthy behaviors leads to normalizing them, and this shouldn’t be needed to feel adored or to fit in.

So please, before reblogging or posting another black and white gif of someone talking about how lovely death is to add to a pale blog aesthetic, think about it.

It’s like handing them a crossbow, showing them how to aim at their heart and saying, “But I didn’t shoot them.”

How To Prevent It

Written by Susannah Mitchell

In the U.S., one person commits suicide every 17 minutes. Every one hour and 37 minutes, an elderly person dies by suicide. And every two hours and 12 minutes, a teenager or young adult dies by their own hand. This suicide epidemic has been going on for as long as anyone can remember. Thousands of Americans are killing themselves each year, and the number is only getting bigger.

Suicide is devastating to anyone involved: friends, family, teachers. Typically after a suicide, anyone close to the person will question their loved one’s motives. Why did they do it? What could I have done to prevent it?

Suicide has many causes. It can stem from different factors depending on the person, such as their living situation, social environment and anything situational that is distressing. The likelihood of a person attempting suicide can depend on their race, gender and religion, as well as identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender (LGBT).

According to Dr. Bill Geis, professor of psychiatry at the University of Missouri Kansas City, there are several elements that are almost always present in a suicide. Any kind of mental condition, typically anxiety or depression, can lead to a pain that some consider unbearable. This might make someone with mental illness more sensitive to loss, rejection, personal disappointment or other social stressors. Recognizing these signs may also help to prevent suicide.

“The general public does not understand that in approximately 70 [percent] of highly lethal attempts, the decision to act is made within one hour of the attempt,” Dr. Geis said in an email interview. “Our studies suggest that people are often in an altered state when this happens, and the person is in no way thinking clearly about their situation.”

East parent and Trailridge Middle School counselor Melissa Wiles deals with depressed and self-harming students frequently. She estimates that, on average, she’ll see six to eight of these students in her office every week.

“I think our world is so fast-paced, so expensive, I just think there’s so many little things,” Wiles said. “Parents [work] and kids are alone. Kids rely on social media, and they can be so mean [to each other].”

One contributing factor to suicide, at least in adolescents, is bullying. Bullying is a known possible precursor to depression in kids and teenagers. In 2013, 38 percent of bullied adolescents had reported suicidal thinking or a suicide attempt the year before. Bullied adolescents are also 3.3 times more likely to consider suicide than non-bullied adolescents.

More commonly, adolescents are using social media to bully. According to the Megan Meier Foundation, it is estimated that 2.2 million high schoolers were cyber-bullied back in 2011. Students, in Wiles’ words, have also started posting about their pain on social media, usually Twitter, which could be an indicator of suicidal intentions.

Wiles also notes that most of the kids she talks to are dealing with one of two kinds of depression: situational or chronic. Situational depression is usually temporary, and occurs after one experiences a particularly difficult hardship in life. Chronic, or clinical, depression is classified as a mental illness, and one that may require therapy and medication. This type doesn’t go away.

Of every depressed, self-harming or suicidal student Wiles sees each year, she classifies the vast majority of them as situationally depressed. These kids will typically leave middle school with a normal mental state. Each year, however, Wiles will have one or two students with clinical depression. These students will deal with depression for the rest of their lives.

In the U.S., up to 3.4 percent of people who are clinically depressed commit suicide, while almost 60 percent of those who commit suicide are depressed or have a mood disorder.

“Frequently, the feelings that an adolescent has are kept incredibly secret,” Dr. Geis said. “We have to make it O.K. for adolescents to come forward with this level of distress and feel like there are interventions that can really make a difference.”

There are many ways one can help someone with depression. However, Dr. Geis suggests letting a well-trained mental health professional help. If one is worried about a friend with potential suicidal intentions, in a school setting, both Wiles and Geis recommend telling someone rather than keeping the information a secret. This would include telling a teacher, a counselor or going directly to the person’s parents.

“Get them help early in the process — before they are in desperate crisis,” Dr. Geis said. “Accurate detection of suicidal risk is not for friends or family to accomplish. Get the person to a well-trained mental health professional.”

Let’s Talk About Suicide

Written by Julia Poe

One year and 135 days ago, I tried to kill myself.

Let me tell you why.

When I was little, words tangled in my brain and I drowned in my own thoughts. I talked to few people, trusted fewer. I was lonely, scared. I grew up, talked more, but even in high school I felt lost in my own mind, crushed by my anxiety.

One year and 135 days ago, I hated who I was. I felt small and vulnerable. In my mind, I was a weak little girl with skinned knees and a watery smile. So I got up in a daze one night, choked down half a bottle of Costco ibuprofen and fell asleep wondering whether God would have blue or green eyes.

I woke up quietly, alone in my bed, wrapped in a blanket of remorse. I cried myself awake and wished I could scrape the guilt off of my skin with my fingernails. My mind was fuzzy, my limbs heavy with self-pity and exhaustion — but I was alive. My parents, asleep in their king bed one room over, were clueless.

Something should have happened. I should have vomited, or at least felt drowsy. Most suicide attempts like mine end up in a trip to the ER. Instead, three hours later, I boarded a plane to Indiana for a church retreat. I’m still not sure why I survived.

I tucked the secret of my suicide into my carry-on bag and vowed to tell no one. I almost entirely kept that promise, only releasing my secret into the hands of my parents and my closest friends.

Until these last few weeks, I didn’t want to write this.

But two weeks ago, two Olathe Northwest students committed suicide. Their deaths were spaced only two days apart. Those deaths stuck in the corners of my mind. I couldn’t stop thinking about it — how those girls died, how I almost died, how anyone might die fighting against themselves.

I first heard about it on Twitter. The suicides were impossible to avoid; they plagued every social media platform and local news station in the Kansas City area. When I first saw the news, I stared at my phone blankly. I replaced the girls’ names with my own. It left a bitter taste in my mouth.

In every article and tweet, I read a recurring theme — no one knew these girls were suicidal. Somehow, tangled up in the daily chatter of homecoming nominations and soccer games and boyfriends, no one noticed these two girls were in enough pain to want to end everything.

Even though I never met these girls, I know a part of them. I know the desperation of feeling that I’m at the end of my life.

But I also know how it feels to start over again.

I know how it feels to wake up after trying to end my own life, look in the mirror and actually see myself for the first time. See flaws, see beauty, see something that is worth staying alive for.

I know how it feels to ask my parents to hide medications where I can’t find them, to go through three therapists before finding one that I trust. And I know how it feels to fall in love with myself for the first time.

I wish those girls had felt that. I wish they had known the pain, the remorse, the poisonous damage of their actions. I wish they had known all the beauty and joy they could still experience. I wish they had lived.

There isn’t enough space in this newspaper for me to properly express my condolences to the friends, the family and the community who were rocked by this loss. But I hope that in watching the Olathe Northwest community grieve the loss of their two beautiful girls, we can also start waking up to a painful reality.

Suicide is everywhere. And it always comes as a surprise.

There is a stereotype that suicide comes in obvious packages. But it doesn’t. The people who kill themselves are also the ones who come to school in J. Crew dresses and cheer in the front row at football games. They are the ones wearing captain armbands on the soccer field and leading the dance team at every game. They are award-winning artists and theatre kids, supportive friends and loving children.

When I tell people my story, I always get the same response. A smile crumbling into shock, a hand on my arm and then that all too familiar phrase — “I never would have guessed.”

That’s the thing. I hid it. I faked it. And I was successful, because even my closest friends couldn’t tell.

We are surrounded by people in hiding, people like me who bury their secrets. We walk the halls at East each day, and each of us think that we are alone in our pain and anxiety and depression.

We need to stop assuming. We need to stop acting like we are all alone. We need to start talking about suicide.

Parents, teachers, friends — learn the signs. Notice when someone begins to pull away. Notice when they stop taking interest. Listen to the people surrounding you, and when something concerns you, confront it head on.

This will be awkward. This will be painful. But in order to save the lives of those you love, you must cherish them enough to talk about suicide.

Talking about suicide is the hardest thing I’ve ever done. But I did it. I told my parents, my friends, Tate. I asked my mom to find me a therapist, who taught me tools to realign the way I process emotions. I stopped worrying about the people who heightened my anxiety, and I slowly learned to love little pieces of myself.

And I’m happy.

That’s why I’m writing this. It’s for those of you who feel you are hiding this pain, who think you are at the end of your lives. I’m begging you — don’t do it.

There are a million and one reasons to kill yourself. But for however many reasons you might find to end your life, I promise you there is always another reason to live.

I don’t know what you will live for. But I know what I live for.

I live for my mom’s chicken and rice casserole. I live for the friends who I can talk to for hours even though we live thousands of miles apart. I live for sunrises in Montreat, North Carolina and for KU basketball games. I live for my mom’s laugh, for Supernatural marathons with my dad. I live for myself, and when that’s not enough, I live for others.

Believe me when I say that life is beautiful. Perhaps death made life more beautiful for me, but I know one thing — there isn’t a day that I wake up that I don’t regret trying to end my life. There’s nothing I can do to change that.

So instead, I try to live with joy and courage and beauty. I am proud of how I live now. I read more and try to worry less what others think of me. I tell my friends I love them and check in on them frequently. I only spend time with the people who truly make me happy.

Sometimes I’m sad. Sometimes I feel the depression trying to creep back, the hate clawing at my chest. But I haven’t thought of death in months. I’m just too happy.

One year and 135 days ago, I thought my life had come to a close. Now, I know that I’m just beginning.

This, Too, Shall Pass

Written by Alex Masson

On July 4, 1998, in the rural town of Kearney, Missouri, fireworks were going off.

While my family was outside celebrating the good ol’ US of A, my Uncle Jim went back into the house to “grab some popcorn.”

He never came back.

At 11:22 p.m., a sound erupted from inside of the house that shrouded itself inside the forest of the countryside. It didn’t sound like the usual dull boom of a firework, as my dad described it. It ripped through the air, leaving a feeling of dread over the party-goers. The people watching the fireworks jerked and looked back to the house, but eventually returned to watching the colorful explosions.

My father and mother eventually went inside the house to check out what the sound was. Possibly a dishwasher was broken or one of the house pets knocked over a cabinet. Eleven minutes later police had surrounded the house. Two minutes later my mother was crying uncontrollably into a police officer’s arms. At 12:02 a.m., my uncle was pronounced dead due to self-inflicted wounds. Also known as suicide.

I was only two months old at the time. I was back at our house in Overland Park, being cared for by one of my aunts, so this is just how my dad described it. Whether some of it is dramatized, I don’t know.

My uncle’s death was instant, a .44 magnum shot through his skull. But my family’s sorrow evaded the treatment of countless shrinks and doctors and still lingers above my household to this day.

I didn’t know about my uncle’s suicide until recently. It must have been one of the things that my parents didn’t feel the need to tell me about until I was older, which I understand. There’s no way I would have understood how big of a deal it was for my parents to walk in on a deceased relative. When I did finally learn about it, I didn’t really care.

But the effects of my uncle’s suicide became evident to me in eighth grade. It was February, just after Valentine’s Day, and my family wasn’t in the best spot economically after my mother was fired from her job. The third time in five years. She didn’t leave her bed for a week, either because she felt embarrassed or disgusted with herself. Any chance to talk about finding a new job or just going out to eat resulted in a conversation full of screaming, cursing and slaps across the face. And tears. Lots of tears.

Eventually, the stress got to her. It was too much to care for me and my sisters. Not to mention she was always getting in fights with my dad over the smallest things. Life became too much of a burden.

She tried hanging herself.

The noose snapped off of the ceiling after my mother had kicked the chair away. The fall left her unconscious, but by some whimsical chance, this is one of the few moments that made me believe there is a god. Unconscious in my parents’ bedroom, with a noose around her bruised neck and a suicide note left in the corner that my father didn’t let me read.

She looked like she was sleeping when I found her.

There was dust on the bed, and a hole in the ceiling. The room was white, with columns of light from the two windows breaking through the dust to illuminate the dirty clothes on the ground. At first, I didn’t say anything. My brain didn’t register what was happening. A rope, a hole, my mother on top of the covers instead of under them.

I screamed and cried, and shook her to wake up. I pawed my way across a desk that sat next to the queen-sized bed that only my mother slept on, knocking over pills and hand lotions until I grabbed a cordless phone through my tear-filled eyes. Eventually I dialled three numbers, and I’ll never forget what the operator said to me.

“Hello, nine-one-one, what’s your emergency,” the voice crackled through the Nokia phone.

“My mother tried hanging herself,” I said in an emotionless tone, something I’ve become known for. Whether I’m super depressed or super excited, I always give that tone now. I guess that’s one way I’ve been damaged by all this.

“Oh god honey. Oh my god.” said the operator, with just enough emotion that you could tell she wasn’t prepared to hear a kid’s voice say that to her.

“Just hold on, everything will be okay. We’re sending an ambulance now.”

It wasn’t all okay. It was far from okay. I was scarred for life, my brain burned with an image of my mother’s lifeless body on the off-white bedsheets.

The next day at school, I didn’t tell anybody. I didn’t tell anybody for two years, until now.

Thankfully, I never went through an “emo” phase, wearing all black clothes and hating every day and wishing it was my last. My other two sisters did. I was emotionally unstable, and I still am, but I learned to find comfort in the little things. Sports, video games, cars.

I bought a Yamaha Ec-12 eterna, a really basic guitar, for $80 from a friend of a friend, though I still haven’t learned how to play the damned thing besides a few chords. I tried everything and anything to push away the thoughts of knowing that mother hated my father so much that she wanted to die above the very bed they sleep upon at night.

“He ruined my life,” I could hear her mutter under her breath after one of their fights.

My sister never found her solace after the attempted suicide. She ballooned to over 300 pounds, had no social life at all and didn’t attend a single college class for about a month.

Then two weeks before my birthday, April 27, she tried to overdose on some prescription drugs she bought from a friend. While it gave her the illusion that she was slowly dying, she really was just going into shock. Twenty minutes later my father came home from work and find my sister foaming from the mouth and twitching on the floor of her own bedroom.

Why my sister tried to take her life, I’m not quite sure. Maybe it’s because of my mother trying to snap her own neck or some deeper social issue that I haven’t heard of. She doesn’t do much, like an old dog that just lays around the house. I think sometimes that while her physical body survived the attempted suicide, she still killed herself mentally.

I’m not going to lie, I’ve had plenty of moments when I seriously considered putting a loaded gun to my head and pulling the trigger. I still do. The only thing that keeps me on this earth is not really me. I couldn’t care less what happens to me, but my friends and my family. I know that if I decide to take my life my dad and mom and all my sisters would be grieving for their entire lives. With the things that have happened to our family, I doubt any of them would be dying of natural causes.

It’s the little things that keep me going, whether it’s going to Starbucks with a girl I have a crush on after the Harbinger deadline to playing old Nintendo games with my friends on a Saturday night. Anything that keeps my mind busy. It’s when my mind has time to think and find the problems in my life that the thoughts come back. You’re stupid. You’re ugly. You’ll never succeed.

Nobody will ever love you.

While suicide is one of the last acts you may ever do, you have to realize that there are people out that love you. That care for you. There are people out there that wake up every day just to talk to you, to see you smile and to hear your problems.

If you decide to kill yourself, somebody will find your body. They’ll find your lifeless body on the floor, the blood splattered on the walls or the noose on the ceiling. They’ll never be the same. Like the two girls recently who committed suicide, and like my story, one person taking their life can take so many other lives with them.

There will always be a better option than suicide. Just remember, as I’ve said to myself countless times.

This, too, shall pass.